This is the second post in a series on Ontario’s loss transfer regime. In the first, “Loss Transfer: New Fone, Who Dis?”, I covered what loss transfer is, where it came from, and some of the challenges it continues to pose.

This article looks at one of my favourite loss transfer issues: fault. Where did fault come from, why do we care about it, and how is it determined?

The Origin of Loss Transfer and Fault Determination in Ontario

The first time I picked up a loss transfer file in 2004, I couldn’t wrap my head around why fault determination was critical in a subset of Ontario’s no-fault accident benefits scheme. Being a history major in my undergraduate studies, I decided to go back in time and trace the origins of requiring fault in loss transfer claims. What I found explains a lot.

In the mid to late 1980s, the Ontario Legislature was developing a no-fault automobile insurance scheme to replace Ontario’s tort-only system. As part of the review process, the government retained The Honourable Mr. Justice Coulter A. Osborne to conduct an inquiry into motor vehicle accident compensation in Ontario. Justice Osborne delivered his report on February 11, 1988, titled Report of Inquiry into Motor Vehicle Accident Compensation in Ontario.[1]

Justice Osborne recognized the problems that motorcycles posed in a no-fault scheme:

F56. Motorcycles present a problem from a standpoint of first party no fault coverage. Those injured on motorcycles being relatively unprotected tend to suffer more severe injuries than those injured in automobile accidents; further the owner/driver population of motorcyclists tends to be young. (237-238)

Justice Osborne proposed subrogation to deal with the “severe premium” issue the no fault scheme would impose on insuring motorcycles.

R103. Because the expanded no fault benefits will provide a relatively severe premium problem for motorcycles, subrogation for motorcycles should be permitted. (590)

Justice Osborne discussed the difference in increased premiums on motorcycle policies if the Legislature adopted subrogation:

In any event, after adjustments have been made on the third party side, without subrogation, motorcycles would be exposed to a premium increase of approximately $85 per motorcycle. With subrogation, the cost/premium increase will be about $31.Because the expanded no fault benefits will provide a relatively severe premium problem for motorcycles, subrogation for motorcycles should be permitted.

In the November 9, 1989, session of the Legislature, the Minister of Financial Institutions advised that the government had accepted the recommendations of Justice Osborne (and others).[2] In June 1990, loss transfer was born from Justice Osborne’s report. His proposed subrogation scheme was codified in section 275 of the Insurance Act and section 9 of Reg 664 – not just with respect to reimbursement, but also with respect to fault – because subrogation depends on fault.

In conclusion, while Justice Osborne’s report primarily addressed subrogation pertaining to motorcycle claims, the loss transfer scheme was broadened upon implementation to include claims involving heavy commercial vehicles.[3]

Why Loss Transfer Indemnification Depends on Fault

Pursuant to Justice Osborne’s proposed subrogation scheme, section 275(2) of the Insurance Act specifies that loss transfer indemnification depends on how much each insurer’s insured is at fault.

275. (2) Indemnification under subsection (1) shall be made according to the respective degree of fault of each insurer’s insured as determined under the fault determination rules.

For example, if the first party’s insured is not at fault at all (0%) and the second party’s insured is completely at fault (100%), the first party insurer can recover the full amount of benefits paid through loss transfer indemnification. If both are equally at fault (50% each), then only half of the accident benefits paid can be recovered.

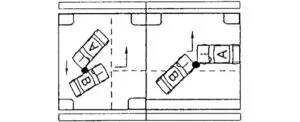

To determine the respective degree of fault of each insurer’s insured, section 275(2) requires us to turn to the Fault Determination Rules, which are codified in Regulation 668 under the Insurance Act. The Fault Determination Rules set out and describe general categories of accidents and scenarios. Some of the rules come with diagrams! The rules then assign fault based on the accident type. This approach typically aligns with objective findings of fault. For example, Rule 6 applies to typical “rear-end” collisions and allocates 100% fault to the trailing vehicle.[4]

The Ontario Court of Appeal has described why we use the Fault Determination Rules to determine fault in loss transfer:

The scheme of the legislation, under s. 275 of the Insurance Act and companion regulations, is to provide for an expedient and summary method of reimbursing the first-party insurer for payment of no-fault benefits from the second-party insurer whose insured was fully or partially at fault for the accident. The fault of the insured is to be determined strictly in accordance with the fault determination rules, prescribed by regulation, and any determination of fault in litigation between the injured plaintiff and the alleged tortfeasor is irrelevant.[5]

In another decision, the Court of Appeal stated that the purpose of the Fault Determination Rules is to “spread the load among insurers in a gross and somewhat arbitrary fashion, favouring expedition and economy over finite exactitude.”[6]

In short, because Ontario’s loss-transfer regime is designed to be fast, predictable, and insurer-to-insurer, fault is fixed exclusively by the Fault Determination Rules to avoid litigating tort issues and turning a summary reimbursement scheme into a full-blown negligence trial.

How Fault Is Determined Under Ontario’s Fault Determination Rules

When determining fault in loss transfer, an arbitrator must first make findings of facts to determine what was the incident. Once the arbitrator determines what the incident was, they must then determine whether the incident is described in any of the Fault Determination Rules. If an incident falls under a specific Rule, the arbitrator must apply that Rule to the incident and assign fault as directed by the rule. [7]

Example: Applying Rule 12 to a Left-Turn Collision

In a loss transfer arbitration, the arbitrator has made the following findings of fact about the incident:

- Matthews was driving his car northbound on Yonge Street in the passing lane approaching Eglinton Avenue.

- Nylander was driving southbound on Yonge Street approaching Eglinton Avenue.

- Matthews made a left-hand turn at the intersection to travel westbound on Eglinton Avenue.

- At the same time, Nylander entered the intersection with the intention to continue driving southbound on Yonge Street.

- Nylander and Matthews collided, causing injuries to Nylander.[8]

Having determined the incident between the two drivers, the arbitrator must turn to the Fault Determination Rules to determine if any rule describes the incident. The arbitrator will notice that Rule 12 describes the incident:

12. (1) This section applies when automobile “A” collides with automobile “B”, and the automobiles are travelling in opposite directions and in adjacent lanes.

Next, the arbitrator will refer to subrule 12(5):

(5) If automobile “B” turns left into the path of automobile “A”, the driver of automobile “A” is not at fault and the driver of automobile “B” is 100 per cent at fault for the incident.

Because Rule 12 describes the incident, the arbitrator applies it and determines that, pursuant to Rule 12(5), Matthews is 100% at fault for the incident. It follows that Matthews’s insurer must indemnify Nylander’s loss transfer claim on a 100% basis, pursuant to section 275(2) of the Insurance Act.

It is very important to remember that if the Rule fits, you must acquit apply it. According to the Fault Determination Rules, Matthews would be considered completely at fault in the example above, even if Nylander had been riding his motorcycle blindfolded while performing a headstand. While this behaviour by Nylander would result in considerable contributory negligence for his tort claim, it would have no impact on the loss transfer claim.

Conclusion: Fault’s Proper Role in Ontario Loss Transfer Claims

Fault plays a central role in the loss transfer scheme. It determines the amount of loss transfer indemnification payable, but does so within a tightly prescribed statutory framework. Loss transfer does not ask who was negligent in the tort sense. It asks how fault is assigned under the Fault Determination Rules, applied to the objective mechanics of the accident.

For insurers, the practical point is straightforward. The loss transfer fault analysis begins and ends with the Fault Determination Rules. That analysis does not change because a tort action is commenced, settled, or tried, and it is not informed by findings made in that litigation. Those findings answer a different question, for a different purpose.

Loss transfer works when fault is treated as the Rules require. When parties try to expand the inquiry beyond the Rules, the process becomes slower, more expensive, and less predictable, without improving the result. Fault drives indemnification in loss transfer quickly and expediently, but only when it stays in its proper lane.

Want more loss transfer? Have a look at our loss transfer decisions.

[1] Attorney General of Ontario and the Ministry of Financial Institutions, Report of Inquiry into Motor Vehicle Accident Compensation in Ontario, The Honourable Mr. Justice Osborne, Commissioner, Vols. I, II (1988), RDB – Tab 1

[2] Ontario House Hansard, Session 34:2, http://hansardindex.ontla.on.ca/hansardeissue/34-2/l067.htm, RDB – Tab 2

[3] Automobile Insurance, RRO 1990, Reg 664, https://canlii.ca/t/565kf

[4] Insurers also use the Fault Determination Rule to determine their insured’s degree of fault under section 263 of the Insurance Act (Direct Compensation – Property Damage) and general

[5] Jevco Insurance Co. v. Canadian General Insurance Co., 1993 CanLII 8451 (ON CA), https://canlii.ca/t/g1k2n

[6] Jevco Insurance Co. v. York Fire & Casualty Co., 1996 CanLII 11780 (ON CA), https://canlii.ca/t/6jvd

[7] ING Insurance Company of Canada v. Farmers’ Mutual Insurance Company (Lindsay), 2007 CanLII 20107 (ON SC), at para 33, https://canlii.ca/t/1rnx7#par33

[8] No Toronto Maple Leafs were harmed in the making of this blog.